Draw Equilateral Triangle In Circle

Introduction [edit | edit source]

In this chapter, we will show you how to draw an equilateral triangle. What does "equilateral" mean? It simply means that all three sides of the triangle are the same length.

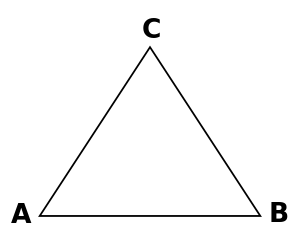

Any triangle whose vertices (points) are A, B and C is written like this: .

And if it's equilateral, it will look like the one in the picture.

The construction [edit | edit source]

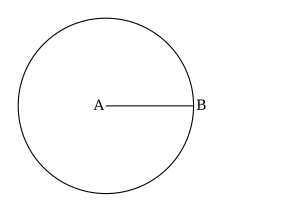

- Using your ruler, Draw a line segment whatever length you want the sides of your triangle to be.

Call one end of the line segment A and the other end B.

Now you have a line segment called .

It should look something like the drawing below.

- Using your compass, Draw the circle whose center is A and radius is .

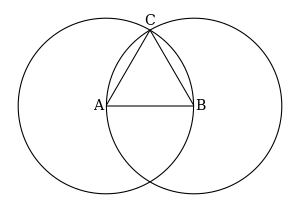

- Again using your compass Draw the circle , whose center is B and radius is .

- Can you see how the circles intersect (cross over each other) at two points?

The points are shown in red on the picture below.

- Choose one of these points and call it C.

We chose the upper point, but you can choose the lower point if you like. If you choose the lower point, your triangle will look "upside-down", but it will still be an equilateral triangle.

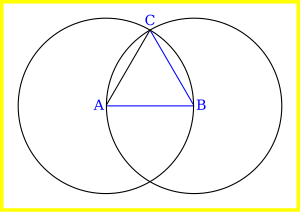

- Draw a line segment between A and C and get line segment .

- Draw a line segment between B and C and get line segment .

- Construction of is completed.

Claim [edit | edit source]

The triangle is an equilateral triangle.

Proof [edit | edit source]

- The points B and C are both on the circumference of the circle and point A is at the center.

- So the line segment is the same length as the line segment . Each is a radius of circle , or more simply .

- We do the same for the other circle:

The points A and C are both on the circumference of the circle and point B is at the center.

- So we can say that .

- We've already shown that and . Since and are both equal in length to , they must also be equal in length to each other. This can be shown by substitution. So we can say

- Therefore, the line segments , , and are all equal.

- We proved that all sides of are equal, so this triangle is an equilateral triangle by definition.

Problems with the proof [edit | edit source]

The construction above is simple and elegant. One can imagine how children, using their legs as compass, accidentally find it.

However, Euclid's proof was wrong.

In mathematical logic, we assume some postulates. We construct proofs by advancing step by step. A proof should be made only of postulates and claims that can be deduced from the postulates. Some useful claims are given names and called theorems in order to enable their use in future proofs.

There are some steps in its proof that cannot be deduced from the postulates. For example, according to the postulates he used, the circles and do not have to intersect.

Although the proof was wrong, the construction is not necessarily wrong. One can make the construction valid, by extending the set of postulates. Indeed, in later years, different sets of postulates were proposed in order to make the proof valid. Using these sets, the construction that works so well using pencil and paper is also logically sound.

This error of Euclid, the gifted mathematician, should serve as an excellent example of the difficulty in mathematical proof and also the difference between proof and our intuition.

Draw Equilateral Triangle In Circle

Source: https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Geometry_for_Elementary_School/Constructing_equilateral_triangle

Posted by: hiserotile1968.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Draw Equilateral Triangle In Circle"

Post a Comment